[ad_1]

On June 9, the national debt surged above $26 trillion. Just over one month before that, the debt eclipsed $25 trillion. And 28 days before that, the national debt stood at a mere $24 million. May’s budget shortfall came in at a staggering $398.8 billion, pushing the fiscal 2020 deficit to $1.88 trillion

And there is no end to the borrowing and spending in sight.

The following article originally published at FEE puts the deficit in some disturbing historical context and explains why it matters.

![]()

The following article expresses the opinions of the authors and does not necessarily represent those of Peter Schiff or SchiffGold.

Even before our nationwide COVID-19 panic attack, we were heading for yet another trillion-dollar deficit. Before the dust settled, 30 million Americans had filed for unemployment, those fortunate enough to have jobs were figuring out how to work from home, and nearly everyone was left wondering whom to trust given the ever-shifting medical advice offered by doctors, bureaucrats, and fools. And all of this was before Officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd, lighting the match that made it seem like 1968 all over again.

Of course, in 1968, the deficit was “only” around $25 billion, and the federal debt was a little under $350 billion. It seems almost quaint given the fiscal cliff on which we now find ourselves.

How high is that cliff? Washington’s finances were bad enough before the recent unpleasantness. But after a round of government stimulus payments unequaled in human history, the Congressional Budget Office predicts a nearly four trillion dollar shortfall for 2020. And that takes no account of possible further stimulus payouts between now and the end of the year. This brings the federal debt to more than $26 trillion. The numbers have become so absurdly large that almost no one but mathematicians really appreciates them. If we were to pay down the debt at the rate of $1,000 every second, it would take more than 800 years to pay it off. The numbers are so large that even the analogies start to require analogies.

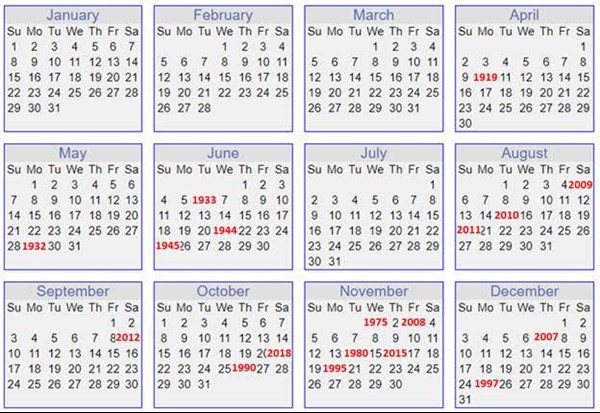

And so we have Deficit Day.

Imagine that the government received all the money it would collect for the fiscal year in one lump sum on January 1, then started spending at a constant rate. The money would run out on Deficit Day. Every penny of federal spending thereafter goes on the nation’s credit card. This year, Deficit Day was June 21, meaning that 193 days of federal spending—over half of 2020—accrued directly to the nation’s debt. This isn’t unprecedented, but the precedent isn’t comforting. The last time Deficit Day fell this early in the year was 1944.

We leave it to epidemiologists to say what might have happened had governors not put most of the nation under house arrest. What we can say is that the lockdown of 2020 has put the federal government in fiscal straits not seen since World War II. But whereas World War II eventually ended, there is reason to suspect that today’s multi-trillion dollar deficits will become the new normal. For evidence, one need look no further than the 2008 crash.

Prior to the 2008 crash, the federal government spent about 14 percent more than it collected in tax revenues each year, causing Deficit Day to land somewhere in mid-November. From 2009 to 2019, that number grew to over 30 percent, pushing Deficit Day back into October. This year, the government is on track to spend 110 percent more than it collects, giving us our first June Deficit Day since World War II. This massive spending will hasten our government’s financial reckoning.

Economists have long been concerned that the debt might grow to the point that interest payments would siphon off an unacceptably large chunk of tax revenues. Unaffordable interest has become less of a concern given historically low interest rates. The new emerging concern is that the gargantuan debt will cause the Fed to lose control of monetary policy.

As trillion-dollar deficits start piling on to the debt, and as the Federal Reserve finances ever greater portions of those deficits through quantitative easings, eventually we’ll get inflation. And then the Federal Reserve will face a hard choice. It can either continue to finance federal borrowing, thereby giving inflation free rein, or it can raise interest rates in an attempt to hold back inflation, thereby increasing the interest expense on the debt. And at $26 trillion dollars, each one percentage point increase in interest rates eventually adds another quarter of a trillion dollars in interest expense every year.

Decades of Deficit Days have brought this upon us. Politicians have no one to blame but themselves for spending us into this hole. And voters have no one to blame but themselves for allowing politicians to get away with it. This will be cold comfort by the time we reach the inexorable conclusion. But with everyone fiddling as Rome burns, there is little else to say.

Consider what it would take first to bring the deficit to zero, then to pay off the debt. If 2020 ends up being an aberration and federal spending returns to pre-2020 levels in 2021, Washington would have to freeze federal spending for almost a decade to get to a balanced budget. And this assumes the economy continues to grow at its normal pace. For the record, federal spending has never been frozen for anywhere near ten years, so we are most likely already into the realm of the politically impossible.

If, thereafter, Congress limited spending growth to the growth rate of the economy, it would take another fifty years to pay off the debt. And this just covers the official debt. It doesn’t include unfunded promises we have made to future Social Security and Medicare recipients. Covering that would take a century or more.

But let’s be honest. There is no way federal spending will return to pre-2020 levels in 2021. The federal government is on track to spend $7 trillion this year. Given what happened following the 2008 stimulus packages, that spigot will likely never be turned off. Even so, if Washington could freeze spending at this new, higher level for the next two decades, the economy could grow enough to give us our first balanced budget somewhere around 2040. If politicians then limited spending growth to the growth rate of the economy, we could reduce the federal debt to zero by some time in the 2090s.

And that’s where we are. We have painted ourselves into a fiscal corner. In the end, everyone—from the Presidents who propose budgets to Congresses that pass them to the American people who demand to receive more but pay less—is blameworthy. The bottom line is that we get the politics we deserve. Sadly, that also means getting the consequences we deserve, which will come to pass when our morass of fiscal policy yields catastrophic monetary policy.

And that will happen soon, because the Federal Reserve is simply out of options. As the Fed simply declares ever more money to exist to cover Washington’s profligate spending, inflation will follow. And there will be nothing anyone can do about it when it comes.

Happy Deficit Day, America.

[ad_2]